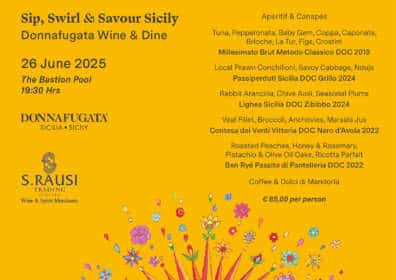

Originally published in Taste December 2009

DAPHNE CARUANA GALIZIA visits the island of Pantelleria for the September harvest of zibbibio grapes and the first steps in the production of Donnafugata’s celebrated passito di Pantelleria – Ben Ryé and Kabir

It’s 40C and the September scirocco which is fouling tempers back home is doing its worst in Pantelleria, which looks on a map as though it has broken away from a straggling Malta and raced ahead to stop 45 miles from Tunisia and 58 miles from Sicily. We are standing in the mid-morning sun in a vineyard from which the zibibbo (Moscato d’Alessandria) grapes have been harvested already, and my predominant thought is of how there is no peace for the wicked who find themselves shuttling between two of the southernmost islands of the Mediterranean in what must surely be the cruellest month. There are several compensations. The hotel, Pantelleria Dream, is just what it says on the tin. The island is magnificent, raw and wild. The smell of the sea is everywhere and the company is most amusing. The food makes me despair at the thought of returning to my kitchen, because it is all seemingly effortless perfection, and the wine is what we’re here to talk about. It’s glorious.

Antonio Rallo of Donnafugata tells me that the day’s conditions will have caused considerable stress to the vines, which nonetheless appear to be bearing up rather better than the human beings standing over them in wilting white linen and dusty sandals. They’re planted out in bowl-shaped depressions in the volcanic earth, which is dark and dry and scattered with pumice. I look around hoping to find something for my bath, but there is nothing of that order, though inky black stones sparkle here and there like the obsidian serpent eyes in that half-remembered, half forgotten Bob Dylan song, Romance in Durango.

The vines grow low on the ground, pruned like shrubs, their leaves and stems trailing into the earth, just as Maltese vines were before organised viticulture and the rise and rise of the estate wine. Nobody can remember vines being grown any other way on Pantelleria, Antonio tells me. It’s done to protect them from the winds which whip across the island in all directions and all seasons – just like they do in Malta, the only difference being that Pantelleria’s topography is without any pockets of protection.

This is a fierce place to grow anything. It is a place where single trees of orange and lemon were protected by tall, round, thick-walled fortresses with lockable doors and an open top to let the owner and the rain in. Some of these still survive. The fortress provided tight protection from the wind and citrus-thieves, and the walls trapped precious dew and cast long shade which kept down evaporation. One tree protected by a fortress provided to a household just enough oranges or lemons to fend off scurvy in the desolate winter. There is no natural water to speak of on Pantelleria, except for rainfall of around 400mm a year. The island is volcanic and there is no water table, no ground water at all. Water for household use is brought in from Sicily. Water for agricultural use appears to depend on how many sacrifices are made to the rain gods. The zibibbo vines are not watered, surviving only on the mercy of the heavens. But they are toughened by generations of survival in that environment and can resist drought better than a camel. Camels, as we have seen from the recent pandemonium in the Australian outback, require water in times of drought and are quite prepared to mow you down and break into your house to get it.

Donnafugata’s Pantelleria estate covers 168 acres. The difficulty is that they’re not all in the same place, but in 11 different parts of the island. The grapes from each vineyard are fermented separately and then blended to produce the Sicilian wine-maker’s lauded passito di Pantelleria, sold under the labels Kabir and Ben Ryé. Kabir I can figure out, but I want to know the reason for the name Ben Ryé. Son of what? I should have known that it wasn’t so much lost in translation as in pronunciation. Son of the wind, I’m told (the wind, of course, the wind): iben ir-rih, bin ir-rih. Pantelleria’s Siculo-Tunisian heritage is as strong as Malta’s, but the difference is that here they don’t quarrel about it. They just take it as read and put it on their wine labels – even though, unlike us back home in Malta, they have long lost the language and must refer to speakers of Arabic to put into words what we know through speaking. One of those speakers of Arabic is busying himself around the vineyard while we talk. He’s been hopping on the boat from Tunis to Pantelleria to help out with the harvest for the last 20 years. There are no prizes for working out that the zibibbo vine, whose raisin-grapes are turned into raisin-wine, gets its name from the Arabic for raisins – not if you speak Maltese, anyway. But there might have been a prize for me there had I not let on that I knew this not through diligent research into the provenance of vines prior to estate visits, but through the simple expedient of speaking a language spawned from Arabic.

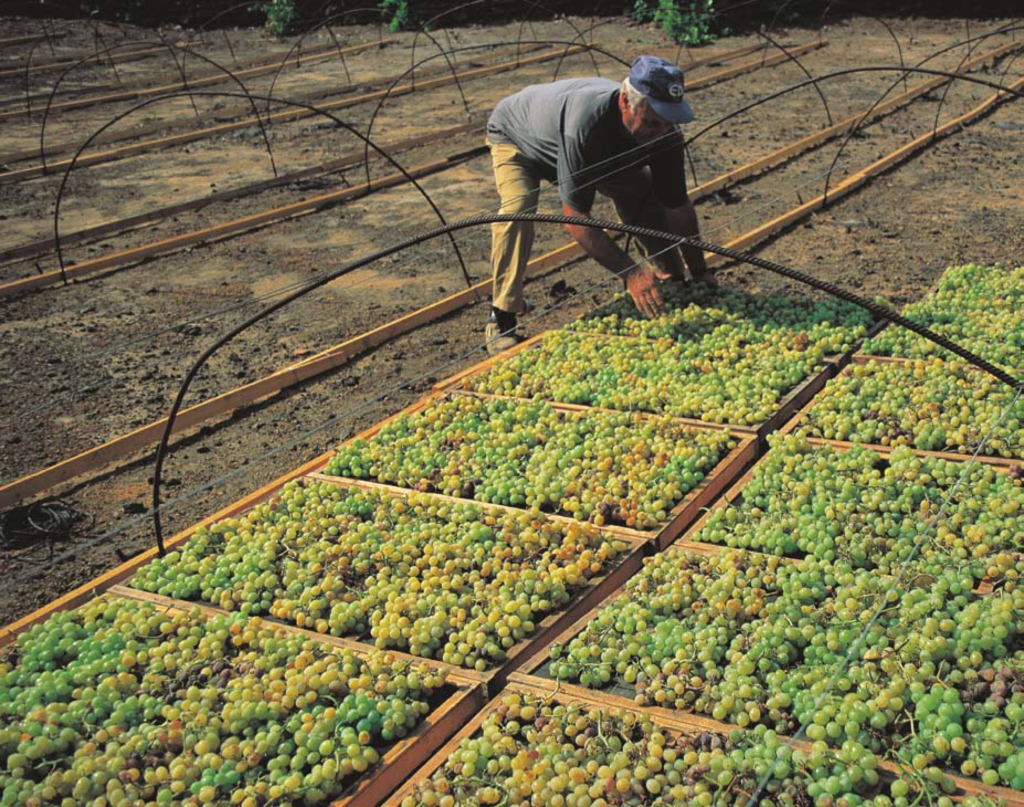

The Khamma winery is a compromise between tradition and innovation. “Tradition is experience,” Antonio says. “There is a reason why passito was made in a certain way for so long. It was the way that worked best. But now there are different ways of dealing with old problems.” I agree that there is no point in mulishly replicating ancient processes which were developed through sheer force of circumstance, in times of deprivation, if today’s world can do it so much better and even improve on the results. There is no virtue in being a Luddite. That devilish scirocco, for instance, the relentless summer heat: most of the time, it’s not the right temperature for wine-making in Pantelleria. It ruins the passito. “So we began using technology for temperature control, which cut down on wastage and lost effort,” Antonio explains.“If there are ways of improving, why not use them? Innovation and tradition need not be in conflict.” And so Donnafugata built its spanking new winery at Khamma, but took care to bring in the sort of architect who would have it blend in utterly with the heart-stopping surroundings. Now tradition at its most basic level – bunches of grapes dried on wooden racks out in the sun and wind, raisins picked by hand off stalks by teams of labourers working between

September and November, pick, pick, picking ceaselessly – works with stainless steel, high technology and sophisticated oenology, like cold maceration and temperature-controlled fermentation.

The people of Pantelleria had been making passito from raisin-grapes for countless generations before Donnafugata got there in 1989. But then Donnafugata got there just in time: Pantelleria’s population was depleted to its present level of just over 7,000. All the young people were doing a Dick Whittington and heading off for bright lights and big cities – and truly, you can’t blame them because shockingly, stunningly beautiful though the island is (it looks pretty much like what Malta must have been 300 years ago, with a few tiny and widely dispersed hamlets lost in great swathes of rough terrain), it’s no place to earn a living or even make a life when you’re 20. There was nobody left to tend the vineyards, harvest the grapes and make the passito – and hardly anyone left to drink it. Even the glamorous French actress Carole Bouquet, who makes passito elsewhere on the island and promotes it in France, was beginning to panic – and when Carole Bouquet panics, the reporters arrive.

Gabriella Anca, Antonio’s mother, used to go to Pantelleria for brief holidays, from their home in Marsala. She understood what a loss it would be if passito di Pantelleria were to fade into history, and thought that the family, who were making wine already at their Contessa Entellina estate in the shadow of the palace central to the Prince of Salina’s life in Il Gattopardo, should get involved. They began with 17 acres and a small cellar. The first vintage of Ben Ryé Passito di Pantelleria DOC was in 1989. Twenty years and many millions of euros later – the Khamma winery alone required capital of €5 million, Donnafugata’s passito di Pantelleria has won 64 awards and has its praises sung far and wide.

This contemporary passito di Pantelleria is nowhere near as heavy as its ancestors. Antonio’s sister Jose tells me that it was devised in response to newly awakened interest in naturally sweet wines. “The consumer was asking for a more elegant dessert wine,” she says. “The older ones had become too heavy and jammy for contemporary taste. We didn’t want to make the sort of wine which people would sip twice and then leave on the table.”

If it’s any help, I can confirm that this one did not get left on the table. It did not even get left in the bottle. It is rich and beautiful, the taste of Christmas, of good times and holidays, of raisins soaked in something wicked exploding in your mouth. Jose remarks about how much has changed in their method since they started out. “And we’re going to try new formulas,” she says. She sips her passito and nibbles at the salted capers for which Pantelleria is also known. She likes the contrast of salty and sweet, she says. It’s how passito is drunk there. Pairing it with puddings and biscuits – sweet with sweet – can be too much, though lots of people love it. Over across the water in eastern Sicily, passito di Pantelleria is drunk with dishes of tuna roe (bottarga) or with cheese.

Back in 1989, most of Pantelleria’s vineyards had been lost already or were well on the way to disappearing: 10,000 acres of vineyards have been reduced to just 1,250. Donnafugata has 168 of them, painstakingly wrested from interminable bureaucracy, archival research, tangled Pantesco family feuds and long-lost emigrants traced to many countries. The big thrill for the family – Donnafugata is run by Gabriella Anca Rollo and Giacomo Rollo, with their son Antonio and daughter Jose – was when they began clearing land to plant out a vineyard and discovered that beneath the almost impenetrable thatch of brambles there was a vineyard already. They had the vines examined and they were

found to be ancient zibibbo that had somehow escaped the phylloxera plague which devastated Europe’s vineyards at the end of the 19th century. There were no signs of grafting to American rootstock, and they were fully indigenous. But it took Donnafugata 15 years to find the owner and then he wasn’t even in Pantelleria. “We tracked him down, persuaded him to sell, agreed on the price, somehow managed to get him to turn up at the appointed hour on the agreed day, and then sat down to sign the contract,” Giacomo Rallo tells me. “He announced that he had changed his mind. So we had to start all over again. To buy another vineyard, a small one, we had to track down no less than 20 people.”

The zibibbo yield is of 1.62 tons of grapes per acre. About four kilos of the grapes go into making a single litre of Ben Ryé; during fermentation, 60 kilos of dried zibibbo grapes are added to every 100 litres of fresh grape must. Production of passito di Pantelleria takes between three and four months. The harvest begins in mid-August, and the best clusters of grapes are laid out on racks and dried by the sun, protected from the heavy dew of thickly damp weather by plastic tents which are open at both ends to let the wind through. It’s not dissimilar to the traditional production of raisins, which is essentially what this is. When we visit the grape-drying zone – large sheets of grapes surrounded by spreading hills and fields and the sea in the distance – the heat is zinging. I begin to feel slight envy for the grapes beneath their flapping tents. “When it’s really hot,” Jose tells me, “the grapes can dry in a day, but the whole drying process must take between three and four weeks.” I begin to think what a good advertisement this would make for sun protection cream: the grapes-turning-into-raisins are beginning to remind me of a few people I know. The idea behind all this drying is to concentrate the sugars and those adorable aromas. By the end, the grapes will have lost some 30 per cent of their weight. Every day, they are turned and inspected for signs of rotting or mould, and the bad ones are whipped out before they corrupt the rest.

The grapes from the second harvest, in September, are pressed when fresh and plump, and the must left to ferment, with dried grapes – which have been picked off the stalks patiently by hand, remember – added at regular intervals. The whole thing macerates, with the raisins yielding their sugar and aroma to the must. At the end of November, it’s put into stainless steel vats and kept there for four months, then bottled and aged for another six months. The result is a wine of extraordinary personality and depth, and its colour – well, that’s just beautiful, like diluted amber. The first intense notes are of apricots and peaches, followed by a turbulence of dried figs and honey; it’s late summer and autumn, rapidly followed by Christmas. It is delicately, expensively sweet and satiny soft, and before you know it, you’re prepared to forgive that damn scirocco anything.